PT | EN

PRIMITIVE ART

Also known as Tribal Art, Art Premier, Ethnographic Art or non-Western Art. In its most basic and least contaminated form, it is the artistic expression that comes closer to the human essence, impenetrable to rational discourse and accessible only by the sensitive way.

It is characterized by the anonymity of the author, where the artist sacrifices the individual attention for the benefit of his community, in a continuous process of construction and affirmation of an identity through the art that is produced. In it we highlight elements of popular tradition of a society, usually organized in a tribal model and therefore almost always linked to the realms of ritual, religion and magic. In general, these artists are self-taught and develop by themselves the tools and techniques they use in their work.

Considered primitive arts are the pre-Columbian Art (Maia, Olmeca), the traditional African Art, the Inuit Art (Eskimo people), the Amerindian Art (indigenous peoples of North America), the traditional Asian Art and the Art of Oceania (Melanesia, Micronesia, Papua), especially from the Australian aborigines.

In the beginning of the XX century, with the modernist movement, primitive and tribal creations became part of the collectable art objects, subject to cataloguing, contemplation and exhibition, even generating an art market and acting as a source of inspiration and renewal for the avant-garde of that time.

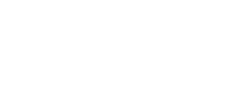

Ritual Masks from african, inuit, amerindian, oceanic and asian peoples.

UNDERSTANDING TRIBAL ART: FROM CREATION TO APPROPRIATION

From the texts “Understanding Tribal Art” (Frederic Godward, 2016) and “African Sculpture from The Collection of The Society of African Missions” (William Siegman, 1980)

«The concept of Tribal art is one of the more controversial topics in the art circles. Another name it goes by – primitive art – evokes myths of colonial superiority, supremacy of Western culture, and looking at artworks from other cultures as intrinsically inferior, only to be observed as a curiosity, a product of an undeveloped society. Despite that, the influence so-called tribal art has had on Western artists in the 20th and 21st century has been so large, has given birth to a plethora of new movements and ways of expression, that it cannot possibly be overlooked, nor viewed as inferior.

Still, the idea of the noble savage is hardly a new one. The beginnings of it can be traced as far back as the Renaissance. During that time, a notion of Arcadia arose, a concept of a utopia set deep in the past, in a vaguely classical Neverland where man lived in harmony with nature. It became a poetic byword for an idyllic vision of unspoiled wilderness. This later evolved into an idealized picture of “nature’s gentleman”, an aspect of 18th-century sentimentalism. American Indians and Scottish Highlanders, as well as various tribes in Africa all played the role of (what the French called) bon sauvage in the minds of the educated city-dwellers of Western Europe.

Up until the 1960’s, tribal art was mostly approached from a purely formalist angle – analyzing and comparing only form and style, without much regard for historical context, symbolism, or the artist’s intention. Luckily, with the advent of postmodernism, this has changed and massive collections in Western ethnographic and natural history museums are being reevaluated and seen in a new light. […]»

Ritual figures from the Zande, Lega and Kongo peoples.

«Unlike the art of Western societies, traditional African art was a functional and necessary part of everyday life and it would be impossible to understand African cultures without an understanding of their art. Religion, government, education, work and entertainment were all closely inter-related in traditional African societies. All of the arts, whether musical, oral or sculptural, were deeply woven into the very fabric of social life and played a central role in binding together all members of the community through corporate activity.

Sculpture figured prominently in the religious rituals which were a central force in African life giving social cohesion through common belief and participation in ceremonial life. The masks and figures used in such rites were not worshipped, however. Rather it was believed that the world was inhabited by many unseen spirits, each with its own powers and personality. These spirits involved themselves in the lives of human beings in a great many ways for both good and evil. The figures or masks were the vehicles through which these spirits made themselves seen and their presence known in the world of men. The objects themselves, however, did not embody or contain the spirit and hence, though respected and honored, they were not worshipped.

African sculpture is new and unfamiliar to most Americans and yet it is the product of ancient civilizations and many centuries of artistic tradition. Initially the masks and figures may seem strange or even grotesque, but when viewed in terms of their own cultures the sculptures of Africa can be seen to be sophisticated, powerful and dynamic. […]»

Pablo Picasso’s and André Breton’s studios, with Tribal Art pieces.

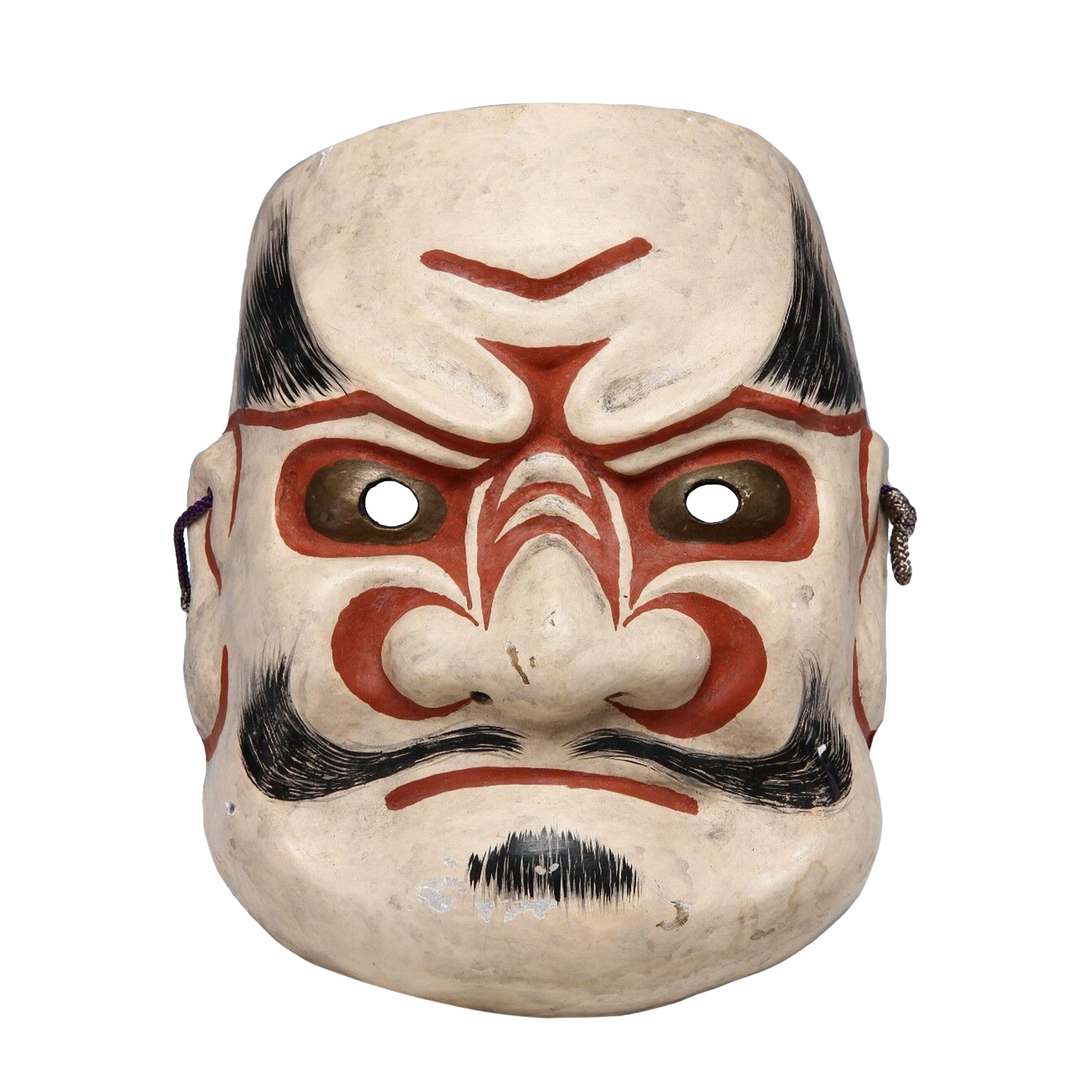

«Around the end of the 19th century in France, while the notions of superiority of “high art” were coming down, a new generation of artists arose that was to soak up the influences of tribal art, completely reinventing the visual language of their time. They took up images from non-Occidental cultures, from folk and naive art and, through individual experimentation, infused them with new meaning. They created a new visual language, very much at odds with the traditionally representational ideals of the academy. Paul Gauguin was the first to run away from modern civilization, all the way to Tahiti. There, his post-impressionist idiom was enriched by the aesthetics of the indigenous people, creating a formula that was to give him a good deal of controversy but also great posthumous fame. Picasso came next and during his proto-cubist period developed a fascination with African masks. They served as an inspiration for his revolutionary canvas Les Demoiselles d’Avignon created in 1907.

Matisse, a life-long friend and rival of Picasso’s, also adopted certain primitivist influences, ideas from art in Africa, as well as those derived from the Islamic culture. His visits to Morocco and Algeria marked an exceptionally fruitful period of his career. Another fauvist, Andre Derain, went through numerous phases, and between his pointilist and increasingly classicist idioms, adopted a primitivist look. Surrealism, arguably the most eclectic style of the 20th century, wasn’t immune to influences from across the globe either. Simple yet poweful shapes taken directly from Africa and Oceania, as well as Indian sources feature prominently on the canvases of Max Ernst from the 1920’s and 30’s, as well as his friend and surrealist André Breton, who found inspiration not only in African Tribal Art – as in the 1948 work Masque Africaine – and oceanic, but also in the North American indigenous art of the Hopi and Yup’ik peoples.

For the remainder of the 20th century, even though not necessarily a part of the mainstream, tribal art remained a source of inspiration for countless artists.»

Works by Pablo Picasso and André Breton, inspired by african ritual pieces.

![]() INFO/LINKS

INFO/LINKS